When the director Errol Morris saw Werner Herzog’s film Fata Morgana for the first time, he was heard to mutter: “I didn’t know anyone was allowed to write things like this.”

I didn’t know anyone was allowed to live like this. Herzog’s new memoir Every Man For Himself and God Against All is astonishing and — whether you know his films or not — potentially life-changing, at least for me.

I made a list as I went along of all the situations in which Herzog has nearly died: in a crevasse on K2; under the hooves of a bull in Guanajuato, Mexico; in a giant wave in Peru; shortly after his own birth, when an Allied bomb hit his home in Munich. After the explosion, his mother picked tiny Werner from the pile of rubble and broken glass in his cradle and found him miraculously unscathed. (He started as he meant to go on.)

While we try to escape reality, Herzog stares into every terrible corner: ‘I’m not afraid of the abyss’

It’s morning in LA when Herzog appears on screen for our conversation. “I think I have lived at least five lives,” he says, looking pleased. “The book could have been a thousand pages long easily but I didn’t want to overdo it.” A door opens and then closes behind him, illuminating his white hair for a moment in the gentle West Coast sun. I think I spot his third wife, Lena.

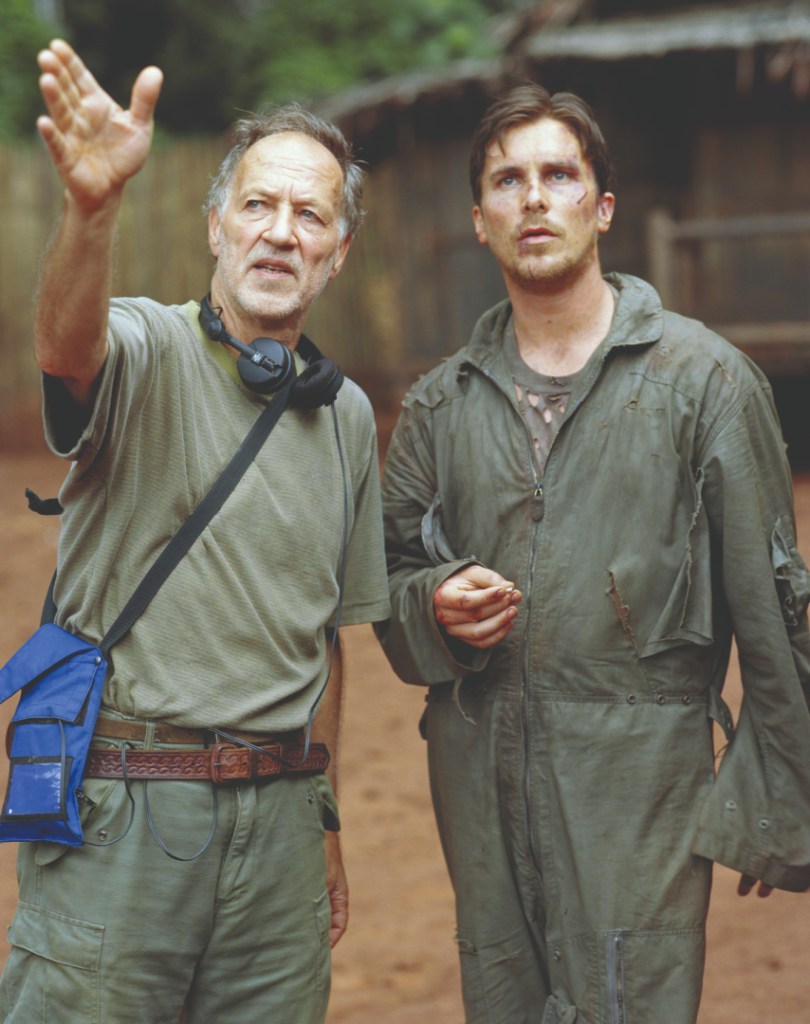

At eighty-one, Herzog is a myth as well as a man. François Truffaut called him the most important director alive. Even if you haven’t seen any of his seventy-odd films, you’ll know of them (Grizzly Man, Nosferatu, Cave of Forgotten Dreams); you’ll recognize his distinctive Bavarian voice and perhaps the crazy fact that in the making of Fitzcarraldo, he hauled a real 320-ton steamship over a steep hill in the Peruvian jungle.

But what’s knocked me for six is the way Herzog faces the world. While the rest of us twist and turn to escape reality, burying our heads in our phones, Herzog stares into every terrible corner: “I’m not afraid of the abyss.”

His vocation seems to have come to him at the age of sixteen. Here’s a quote from the book to give you a sense of the man. He was on a skiff late at night in Crete, he writes, catching cuttlefish.

And below me, lit up brightly by the carbide lamp, was the depth of the ocean as though the dome of the firmament formed a sphere with it. Instead of stars, there were lots of flashing silvery fish. Bedded in a cosmos without compare, above, below, all around, speechless silence, I found myself in a stunned surprise. I was certain that there and then I knew all there was to know. My fate had been revealed to me… I was completely convinced I would never see my eighteencth birthday because, lit up by such grace as I now was, there could never be anything like ordinary time for me again.

“What exactly was this fate that was revealed to you?” I ask, aware that I probably shouldn’t.

“It’s not easy to recall it precisely,” says Herzog, “but it has carried me very far, probably some sort of knowledge that I was a poet and that I would probably have a difficult life which I had to shoulder and it cannot be described easily.”

“Is it a feeling that you are going to have to suffer pain?”

“No, it’s not pain, it’s just a difficult life. I think if I tried to explain I would just simply talk it apart into smithereens. It is good as it’s described, you should leave it as this here.”

Herzog converted to Catholicism as a teenager and, though he doesn’t now believe in God, the man who emerges from his book seems almost Biblical. He walks and talks with the world the way Abraham and Job walked and talked with God — sometimes railing against injustice, never defeated.

There’s a striking moment in Burden of Dreams, the film about the making of Fitzcarraldo, when Herzog, who has been filming upriver, deep in the jungle for years, turns to the camera: “There is no harmony in the universe,” he says. “There is no order. The only harmony here is the harmony of collective murder. When I say this, I don’t mean I hate the jungle. I love it against my better judgment.”

Like an Old Testament prophet, Herzog often sets off on foot and just wanders the world. He doesn’t have a phone: “Text messaging is the bastard child handed to us by the absence of reading.” He just picks up a satchel, one given to him by the travel writer Bruce Chatwin, and walks, sometimes for hundreds of miles.

He says to me: “I think I have this in common with Bruce Chatwin, for whom it was one of the central ideas of his existence, that the end of traveling on foot was basically the abandoning of the nomadic life and that all the woes of the human race emerged from that transition into a sedentary life.”

“But people still travel,” I say.

Herzog raises his eyebrows: “You have backpackers but that is different, they carry their whole household, their tent, their sleeping bag, their cooking utensils, their food, everything — but traveling on foot the way Bruce Chatwin would do, I would do, is something different.”

“Why travel without a backpack? What’s the sense?” I feel defensive on behalf of the involuntarily desk-bound.

“Well, the strange thing is the world starts to trust in you. Because when you are thirsty, it’s a hot summer day and you run out of water and your canteen is empty by some time in the afternoon and there is no creek or anything around, you have to knock at the door of an isolated farmhouse and the startled wife of the farmer opens the door and you ask her, ‘Can you fill my canteen with water, I am very thirsty?’ Of course if you are polite you will stay outside the door and you bow and you have the right tone. Then comes the question, ‘Where do you come from?’ I would say I come from Munich. ‘But that is 1,200km away, how did you get here?’ And I said, on foot. From then on, there is an ancient reflex of hospitality and it is still enough in a way.”

“So the walking is important both for you and for the people who give you shelter?” I say. “If no one knocks on the door, people never get a chance to be hospitable?”

“Exactly — it’s dormant, hospitality is something very ancient that is dormant and I have seen it without exception, without any exception.”

It’s when he’s out walking that Herzog often comes upon the scenes that later inspire his films. As a young man, he walked the length of Crete through the mountains of the interior, and came across a wide valley full of thousands of windmills, which in the end became the central image for his first feature film, Signs of Life (1968).

“At the time it was alarming, because what I saw was a valley of 10,000 windmills speaking. It is something that cannot be, unthinkable, it’s unheard of, so there is something not right with me and until I realized, yes, everything was right with me, only the field with 10,000 windmills had gone berserk.”

“What does it feel like to be struck like that by something?”

“It becomes part of your soul. It’s not a vision, it’s not just a thing that you store in the memory of your cellphone by taking a picture, it is something much deeper. I think that is what poetry is all about, something that becomes part of us in it and I return it back in a different form.”

“So art is a sort of alchemy? You take in reality and transform it?”

Herzog shakes his head: “We shouldn’t speak too much about art and artists and all that because I have no real sense of art and artists. It’s strange for me that you think I’m an artist.”

“Of course you are.”

“I think I’m a soldier.”

After she picked Werner from the debris of that Munich bomb, his mother fled with her two boys to the countryside. She had connections in the Sachrang Valley in remote Bavaria, so that’s where they went, and that’s where Werner and Tilman grew up, freezing, often half-starved but completely free.

How would his brother describe him? “Taciturn, withdrawn, thinking, brooding on simple mathematic patterns — why was eleven by seventeen the same as seventeen by eleven? I do believe I could have become a mathematician but it’s hard to say.”

‘Hospitality is something very ancient that is dormant and I have seen it without exception’

It’s clear that from a young age, Herzog was also possessed of unusual will power. He describes a time in which he and Tilman were clutching at their mother’s skirts, whimpering with hunger, and “with a sudden jolt, she freed herself, spun round, and she had a face full of anger and despair I have never seen before of since. She said perfectly calmly: ‘Listen, boys, if I could cut it out of my ribs I would cut it out of my ribs, but I can’t, all right?’ At that moment we learnt not to wail. The so-called culture of complaint disgusts me.”

“How old were you then?” I ask.

“I must have been five maybe.”

Even though he was so young, he resolved not to complain? “You understand. In such big moments you understand very, very clearly. When you look around, the education of children is infantilized. Children at age five know much, much better and much quicker than anybody today might think.”

There was another moment in the Sachrang Valley when young Werner exercised his will. In a fight with his brother Tilman, he felt a murderous rage and drew a knife. He cut him, hurting him quite badly, and then, horrified by his own actions, decided never again to let his anger escape. He writes: “Instantly, I understood that I would have to change my ways immediately and profoundly.”

I ask about it now, interested in how much of Herzog’s character is an act of will. But I’m surprised to see how much the memory disturbs him. He looks deeply sad, as if he hurt Tilman just a few days ago.

“Yes, it is awful to speak about it… I describe it, but it still pains me when I think about it.” I try to console him. “We’re all terribly flawed,” I say. “At least you made an act of will to change.”

“It’s a question of discipline, of control, and it’s as simple as that,” says Herzog. “Do you find it strange that the world is full of people without willpower? No, it’s not will — it’s a clear decision and you stick to it.”

“Do you feel humans are more good than bad, would you say?” I ask. I can’t think of anyone who has seen more of the world or who is better placed to judge.

“Oh no, don’t start with that!” he says. “We shouldn’t, you shouldn’t even attempt it.”

Throughout our conversation Herzog’s eyes have stayed lowered. I’ve read that he rarely looks in the mirror, but I don’t ask why, for fear of sounding like a shrink. “I’d rather die than go to an analyst,” he writes in his book. “I am quite convinced that it’s psychoanalysis — along with quite a few other mistakes — that has made the twentieth century so terrible.”

Herzog is sure of his significance. “I am aware that I possess an almost absurd self-confidence, but why should I doubt my abilities when I see all these films so clearly before my eyes?” he told Paul Cronin, author of Werner Herzog: A Guide for the Perplexed. He tells me: “The book will live longer than my films. You can see it in my prose, the way I write.” Is he writing another book? “I have just finished my next book which is going to be published, it is called The Future of Truth. It has a beautiful title.” It’s a terrifying title too, I say. Truth is becoming such a strange thing, isn’t it? “Yes, I’m dealing with it.”

But the idea that Werner Herzog is an egomaniac or a narcissist seems to me wildly off-beam. He’s too alive to the world, too sympathetic.

“I was so impressed by your book that I’ve resolved to bring up my son differently,” I say. “I’ve made some notes” (and I have).

“No, no, no, come on!” For the first time, Herzog looks up. “Please bring up your son according to the historical environment, according to your possibilities, according to the culture in which he is growing up, so don’t try to imitate anything that I describe, no, no, no. Just bring him up as well as you can in your environment.”

“But as you say, a real man needs to know how to do things like milk a cow.”

“It’s much easier than that. Your son doesn’t need to know how to milk a cow. I’d allow him to dig a deep hole in the ground. Just let him dig a hole in the ground.”

Herzog’s friend the physicist Lawrence Krauss has said: “Ultimately, the Werner Herzog I have come to know is not the wild man of his press clippings. He is a caring, thoughtful, playful and essentially gentle human being… interested in all aspects of the human experience.”

When Werner was thirteen he saw images of cave paintings for the first time, in a bookshop window. He says now: “I felt a deep shock of awe which in a way — and I am careful to use the word but I say it anyway — awakened my soul. I say this with a pair of pliers because it sounds pretentious but it’s not. It was such a deep shock of awe, and the sense of awe has never left me in anything that’s around me. I don’t know what it is exactly but it’s very deep, it’s one of the things that make me into what I am and it has never stopped.”

Then he says suddenly; “Is this part of The Spectator’s Christmas edition or whatever? That’s what I was told. Yes, well, Merry Christmas to everyone!”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.