Some of Pope Francis’s closest allies in the Catholic Church are alleged to have secretly given more than €2 million to an Italian migrant rescue charity whose senior staff are charged with people smuggling. They include Cardinal Matteo Zuppi, archbishop of Bologna, who is among other things the papal peace envoy to Ukraine, and Cardinal Jean-Claude Hollerich, archbishop of Luxembourg. These senior figures in the Church organized payment of the money, it is claimed, at the bequest of the Pope who had established a special rapport with the far-left founder of the charity. The payments were kept secret for fear of adverse publicity.

The disclosure has been made in internet chatroom conversations between members of the charity’s staff, recorded on the orders of prosecuting magistrates in the Sicilian city of Ragusa, as well as in seized documents. Transcripts of the intercepted conversations and copies of the documents were subsequently leaked to the Italian weekly, Panorama, which has since published them. The Church allegedly continued to make the payments, which began in August 2020, even after the news in March 2021 that the Ragusa magistrates had placed senior staff at the charity, Mediterranea Saving Humans, and the company that owns its rescue vessel Mare Jonio under formal investigation for people smuggling.

On Wednesday December 20, the Pope responded to the media storm the Panorama story has unleashed in Italy with a remarkable show of defiance. Luca Casarini, the founder of Mediterranea, was joined by his colleagues in the crowd at the Pope’s final weekly general audience before Christmas at the Vatican. The Pope did not mention the money the Church has given Mediterranea but at the end of his speech on the significance of the nativity scene he singled out the charity for a special mention. He added: “I also salute the group from Mediterranea Saving Humans, who are present, and who go to sea to save the poor people who are fleeing slavery in Africa. They do great work: they save so many people.” After the audience, Casarini went on stage to shake the Pope’s hand.

That is not exactly true. This year its rescue vessel Mare Jonio has carried out just two rescue missions both in the same week in October. Regardless of the Mare Jonio’s inactivity, the Church has given the charity, it is claimed, about €1 million in 2023 — four times the sum paid in 2021. Much of the money is said to have come from donations given by the faithful at Mass, or to their dioceses, or else directly to Peter’s Pence — the Pope’s fund for worthy causes.

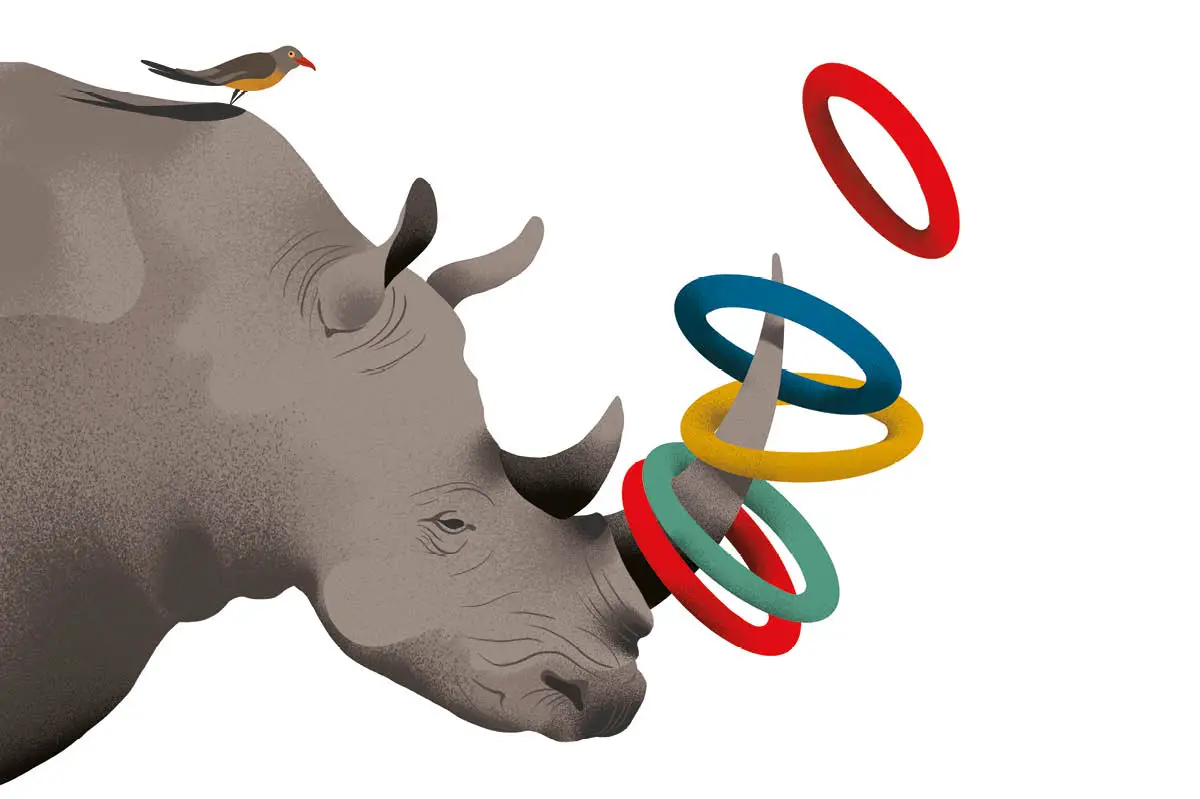

Casarini and five others are charged with using Mare Jonio to bring twenty-seven illegal migrants to Italy in September 2020 in return for €125,000 ($138,000). The money was paid to them by the Danish owners of a merchant ship that had rescued the migrants and then handed them over to Mare Jonio. In an intercepted conversation just before the deal was struck, Casarini tells colleagues: “This time tomorrow we can break out the Champagne because we’ll have the reply from the Danes.” That the payment was made is not in dispute — but the accused say it was to cover expenses. The opening hearing of the case was due to take place earlier this month but has been adjourned until February.

It was only thanks to the Ragusa people smuggling investigation that details of the payments by the Church to Mediterranea came to light. But the payments are not being treated as penally relevant — at the moment. They are nevertheless deeply embarrassing for the Pope, as well as the cardinals and the dozen or so archbishops involved.

It was only thanks to the Ragusa people smuggling investigation that details of the payments by the Church to Mediterranea came to light.

Casarini, fifty-six, is a former leader of violent protests against global capitalism. He has an impressive criminal record as he proudly posted online in 2016. Until recently, he was a strident atheist or “mangiaprete” (priest-eater) as the Italians call them. But in 2019 — one year after founding Mediterranea — Casarini miraculously found God and installed a chaplain on board the Mare Jonio, don Mattia Ferrari. The ship’s chaplain used his contacts to get Casarini a vital audience with Pope Francis in December 2019 at the Vatican. He presented the Pope with a life jacket nailed to a cross which is now on display at the Apostolic Palace. Casarini then wrote the Pope a letter in April 2020, published in the bishops’s daily, Avvenire, full of passionate talk about his efforts to save migrants in the Mediterranean to which the Pope replied in the same newspaper: “Luca, dear brother… Thank you for all that you are doing… You can count on me.” This October, Casarini was one of just three special lay guests invited by the Pope to participate in the latest session of his cherished Synod of Bishops, of which Cardinal Hollerich is Relator General.

There are many references to the Pope’s involvement in the operation to give money to Mediterranea in the internet chatroom intercepts. Of Casarini’s audience with the Pope, the chaplain don Mattia who was also present reportedly tells the others that “the Catholic Church is becoming our Soros” and “I am still recovering from the effort that I made to find the balls to tell the Pope to hand over the money.” He’s also quoted as reminding the group: “Don’t forget that at the private audience… Pope Francis openly said that he would support Mediterranea.”

In a telephone conversation, recorded by don Mattia and posted in the chatroom, Cardinal Zuppi tells him that Cardinal Konrad Krajewskij, Papal Almoner in charge of dispensing charity money on behalf of the Pope such as that from Peter’s Pence, is doubtful about donating to Mediterranea. “We must find a way to convince Krajewskij. He needs to receive the mandate directly from the Pope,” Cardinal Zuppi, who is considered Papabile (a possible future Pope), reportedly tells don Mattia. Casarini was only able to launch Mediterranea in 2018 thanks to a €460,000 overdraft facility granted by the Banca Etica that was guaranteed by a number of left-wing and far left Members of Parliament. But he soon ran out of money.

That Pope Francis should want the Church to back NGOs that bring migrants across the Mediterranean to Europe is hardly surprising — however fast and loose they and their rescue boats play with the law. This September, for instance, the Pope was in Marseille to attend an international meeting on the migrant crisis where, during a ceremony at the city’s memorial to migrants who have died at sea, he said that they “must be saved” because it is “a duty of humanity.” Casarini was present and embraced the Pope who was in his wheel-chair before kneeling in front of him. This was just days after the tiny Italian island of Lampedusa was overwhelmed by the arrival of 12,000 migrants in less than a week. But to back someone like Casarini would surely be just asking for trouble.

I discovered that Mare Jonio has only done five rescue operations in the three and a bit years that it has received the backing of the Church. They include the mission in 2020 that led to the people smuggling charges. That the Church has given hundreds of thousands of euros to Mediterranea cannot be denied as the charity’s own accounts, published on its website, reveal that “enti ecclesiastici” (ecclesistrical bodies) gave it an unspecified sum in 2020, €219,000 in 2021 and €275,736 in 2022. The only dispute is over how many hundreds of thousands it was and who authorized it.

In a brief statement, the Italian Episcopal Conference (IEC) – of which Cardinal Zuppi is president — admitted that the Catholic Church had given money to Mediterranea. But the IEC denied that it has been “directly” involved in doing so, though it had “agreed” requests to give money to the charity from “two dioceses” which it declined to name. These had given the charity €100,000 each, it added, “in 2022 and likewise in 2023.” It described the intercepted chat-room conversations as “defamatory” of “ecclesiastical people and institutions.” But that hasn’t stopped the story buzzing around the Italian media in recent days.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.