The village we moved to in central Italy is lovely — old stone houses and olive trees on a hillside — but it is eerily deserted most of the time. A neighbor in his forties says that when he grew up here, it was full of children playing in the cobbled streets. There were about 350 people then, he tells me; now the population is precisely forty-two, and that includes the latest residents, me and my wife. The village is dying on its feet, becoming a perfectly preserved museum piece. My neighbor shakes his head and says how sad it is. There are many villages like this in Italy. First one house is boarded up, then another; the trattoria closes, after that the bakery and other shops, and then people leave all at once because the place isn’t what it was. Some mayors are famously offering newcomers houses for just €1. This makes almost no difference because of something that is happening across the whole country: Italians are not having as many babies as they used to.

At the peak of the post-war baby boom in Italy, in 1964, there were a million births. In 2008, 600,000 babies were born; last year it was 400,000. That’s a fall of a third in the past fifteen years alone. The most important figure of all is this: there are now, on average, 1.24 births for every woman in Italy. That’s way below what would keep the population as it is: two babies who reach adulthood for every woman. The country is graying. You can see it. Italians have invented a word, umarells — “little men” — to describe the old codgers standing hunched outside building sites, hands behind their backs, offering unwanted advice to the hardhats. For every Italian who joins the workforce, two retire. Schools are closing. Playgrounds are empty. The pension system faces bankruptcy. The most profound effect of the low birth rate is that the country is shrinking. Today’s population, 59 million, could be 54 million by 2050, 47 million by 2070. One newspaper headline here said: “The last Italian could be born in less than 200 years.”

The Italian prime minister, Giorgia Meloni, says there’s no higher priority for her government than ending the nation’s “demographic winter.” She has even created a “minister for the birth rate.” She invited Elon Musk to Rome in December to talk about this — it’s one of his favorite issues. He said: “Italy is the people of Italy… make more Italians to save Italy’s culture.” This country, once known for its large families and love of children, offers a glimpse of the future for the rest of Europe. France has a birth rate of 1.8, Germany and the UK 1.6, Spain 1.2 — all far below the replacement rate of 2.1. And it’s not just Europe. The United States has a birth rate of 1.7. Even in South America, they’re not having enough babies to maintain the population: Mexico’s figure is 1.8, Chile’s 1.5. In Asia, Japan and Thailand are at 1.3. The country with the lowest birth rate in the world is South Korea, at 0.78. This means the number of babies born in South Korea will halve every twenty years.

That calculation was done by a British demographer, Stephen Shaw. He has made a thought-provoking documentary about population collapse, which you can see at birthgap.org. Before he started digging into the figures, Shaw thought population growth was the problem. That’s been the relentless message since the 1960s, with dire warnings of a “population bomb,” a Malthusian nightmare of exponential growth in human numbers that could overwhelm the planet and lead to mass starvation. India took this so seriously that 8 million people were forcibly sterilized; China had its one-child policy. It’s not surprising that a conventional wisdom persists that overpopulation is the greatest danger we face — a few choosing to be childless “for the planet” — because the number of humans is still growing: 8 billion now and probably 10 billion by the middle of the century. A lot of this comes from high birth rates in the Middle East — women there have three babies, on average — and above all in Africa: there are six babies for every woman in Chad or Mali, five in Nigeria. But Shaw says birth rates in developing countries are falling rapidly and they could be like everywhere else in a generation or two.

In many of the rich nations — paradoxically, given their low birth rates — population is growing slowly and will contribute to the rise to 10 billion. Shaw says that’s because people born during earlier baby booms are still getting old. First, population growth slows, and the proportion of old to young increases: an “inverted world.” Then population starts to fall and — just like growth — the decline compounds exponentially: an empty world. Italy, Spain, Japan and South Korea are already on the “wrong” side of this curve. But, I ask him, couldn’t we imagine a better world with fewer people in it? AI and robots could do the jobs left vacant by missing workers. Houses would be cheaper. Shaw says that robots don’t pay tax. There would be enormous economic upheaval. And with fewer people you don’t just get more space to spread out, you get decaying cities, such as Detroit, where he used to live. At the very least, it will be “a very bumpy journey” with lots of lonely old people and no one to look after them. Worse than that, Shaw believes that societies find it nearly impossible to recover from very low birth rates, entering a kind of death spiral. “We don’t know how to stop this descent, and it’s accelerating.”

What’s causing this? A change in the culture — more couples making a lifestyle choice to remain childless? Or economics? In some parts of Italy, for instance, half of young adults can’t find a job. Young Italians often live at home with their parents, into their late twenties and early thirties, rather than marrying and starting families of their own. Shaw’s research uncovered a clear link between economic recessions in industrialized countries and declining birth rates, though it’s not as simple as people feeling too poor to start families. Birth rates dropped after the oil shock of 1973 and the banking crisis of 2008 — but when the economy recovered, people did not start having more babies. Each recession caused a reset in the culture. Shaw has gathered the statistics to explain why. They reveal a startling picture of the way we live now.

Shaw says that despite low birth rates, families are not getting smaller. If a couple does start a family, it is likely to be as big as in decades past: “Motherhood has been incredibly resilient.” However, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of childless couples. This is not, as you might think, because people are choosing career, money and freedom over children: only a tiny minority want to be childless. Eight or nine out of ten people say they want children — but they are waiting longer to have them. That choice seems logical in times of economic uncertainty and then becomes the norm. But Shaw says the crucial overlooked fact is that only half of women who enter their thirties without having started a family will ever become mothers. Many wait for their careers to develop, or they’re still looking for Mr. Right. They don’t realize how steeply fertility declines, how little time they have.

The statistics conceal an ocean of hurt. On Facebook in Italy, you can find groups to support women who do not have children, whether by choice or accident. In one forum, a woman tells a typical story, posting anonymously because this is deeply personal, and painful, and because women feel judged for being childless. She says she was careful not to get pregnant in her twenties because that would have meant “the end of all her projects”: university, travel, career. In her thirties she started to try for a baby and was relieved at first when nothing happened — life was so busy — but then she started to feel increasing “dismay and loss.” Now, approaching forty, she is left with the “small, weak hope” given by fertility treatment. This is a “murderous path” strewn with jabs, tests, hormones, weight gain, side effects and, by now, three failures. “Three knives to the heart.” Shaw says young women must be told that waiting to start a family risks “unintended, unplanned” childlessness. “We teach young people how to not get pregnant. We really don’t teach anything meaningful about the fertility window.”

Giulio Meotti, a columnist on the conservative Italian newspaper Il Foglio, would go further. He says the whole country should be talking about the birth rate. Too much time has been lost failing to address this “taboo” subject because of its association with fascism: Italians remember that Mussolini encouraged more babies “for the Homeland.” Prime Minister Meloni and her government might be raising the issue now but he tells me it’s “cheap rhetoric” when — in his view — so little money is spent to support the family. He worries that Italy does not have “the stomach” to do what must be done to turn things around. Part of the problem, he believes, is that Italy is no longer a Roman Catholic country and religion is important for a people’s identity. Italy is suffering a “cultural malaise,” even a “spiritual” decline. “Babies are not just a private issue. It’s a national question. We have to say [to women] your uterus is not just your business. The collective future is at stake.”

If that sounds like something from The Handmaid’s Tale, Meotti is at pains to stress that he does not want to drive women back to the kitchen. He would like to see business and the state doing more to help women both to work and be mothers. He wants economic measures, certainly, but he wants attitudes to change, a new “cultural vision” for Italy. He is against solving the demographic crisis through more immigration — “the national dogma of our media and the elite” — because that too would threaten Italy’s cultural identity: the numbers needed would be so huge. He points out that Italy has had more deaths than births for more than thirty years. It is now one of the oldest countries in the world, along with Japan and South Korea. “I’m very pessimistic… We are in serious trouble… waiting for the inevitable. It’s a slow suicide.”

All this is based on projections. It is possible that the predicted exponential downward curve of population could flatten out, that people might just decide to start having more babies again. But for Italians — and for everyone else — there is a warning from history. One theory of why the Roman Empire fell is that there was a low birth rate. For a time in ancient Rome, you could be fined for not having a child. The collapse did not happen overnight, but over generations, centuries, until one day the Colosseum was empty of cheering crowds, and peasant farmers moved in to keep their cows under the arches. If it is true that “demography is destiny” then our civilization, too, might disappear, not overnight, but slowly, almost imperceptibly from one year to the next, until we simply fade away.

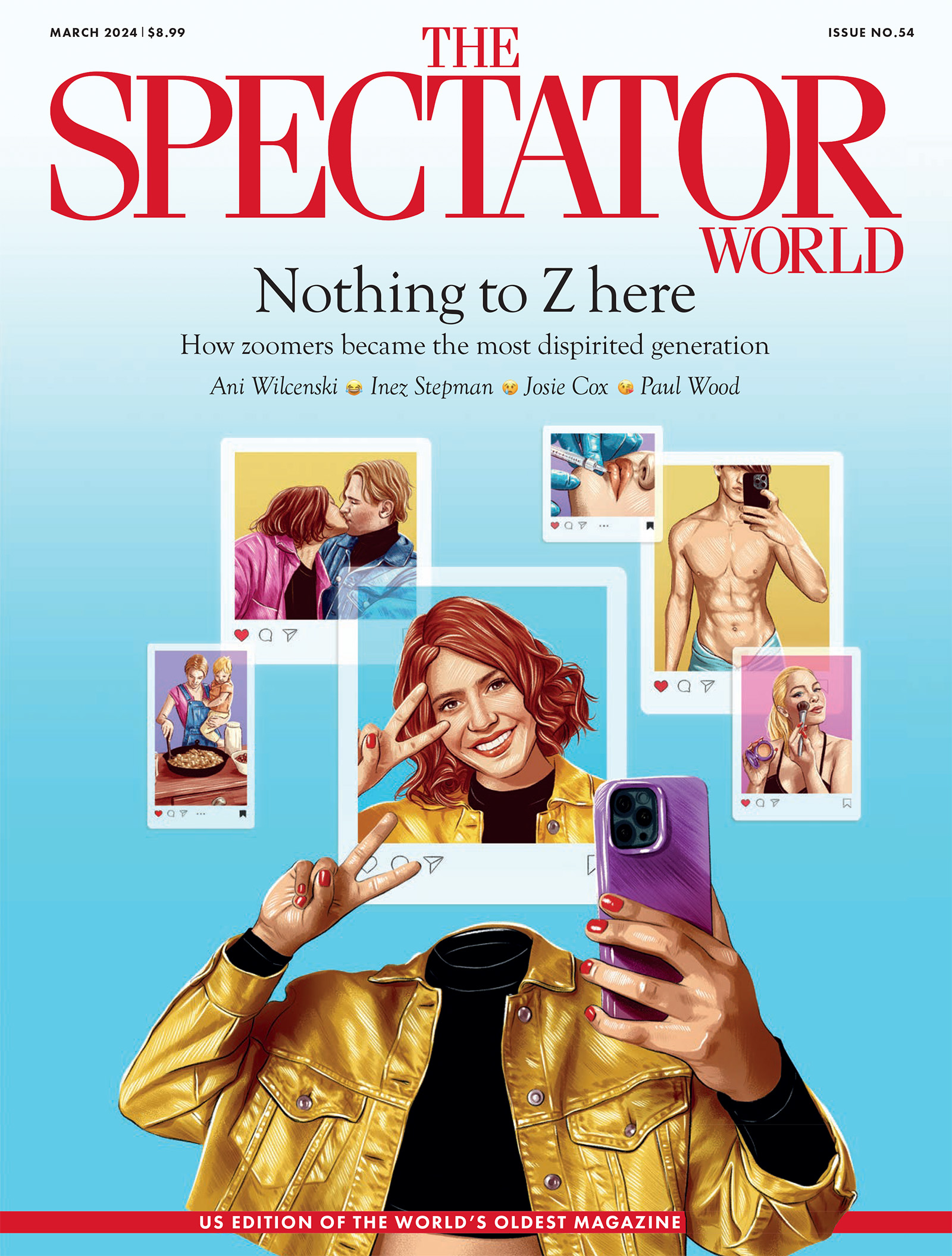

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2024 World edition.