Several hundred years ago, in the 2014 film 20,000 Days On Earth, Ray Winstone asked Nick Cave: “Do you want to reinvent yourself?” Cave, looking out from his sunglasses, replied: “I can’t reinvent myself.” “Do you wanna?” “I don’t want to either. I think the rock star’s gotta be someone you can see from a distance. You can draw them in one line… They’ve got to be godlike. It’s all an invention. But it happened early on for me.”

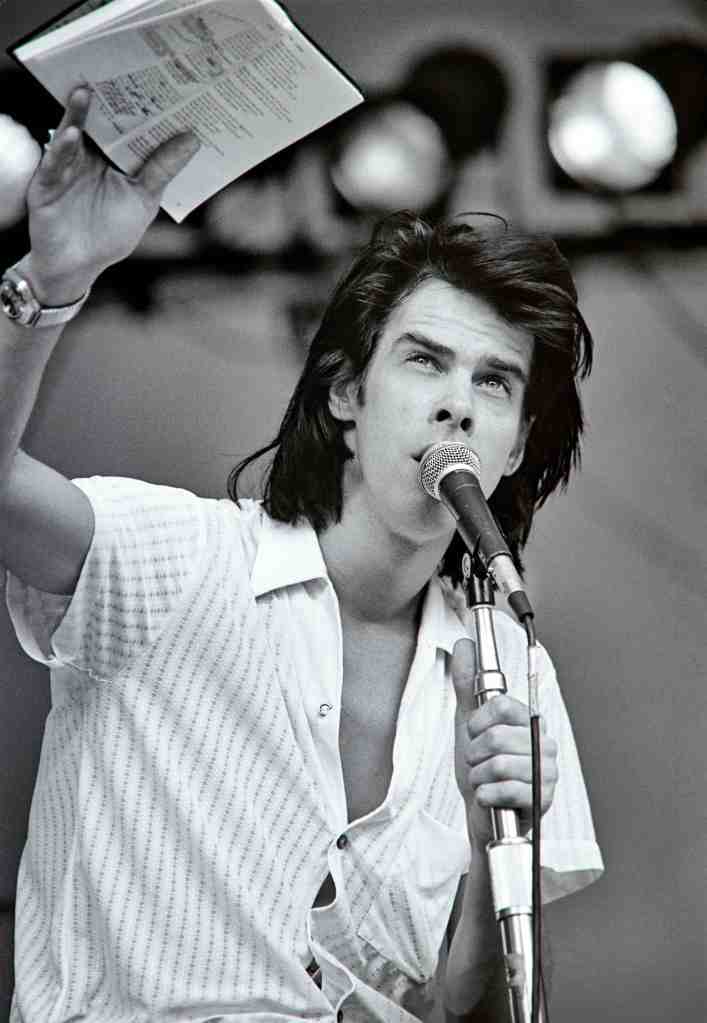

On the handful of occasions over the years that I’ve seen Cave from a distance, he has been just that sort of figure — one a deft cartoonist would draw with one line: ski-jump nose, Sesame Street eyebrows and a swept-back bob of jet-black hair like Wednesday Addams after Uncle Fester chopped off her pigtails for a prank. And always, always immaculately tailored. In the new book Faith, Hope and Carnage, an edited collection of interviews with the writer Seán O’Hagan, he tells the story of getting busted by the New York cops after scoring heroin in Alphabet City wearing a “lime-green three-piece suit.”

We meet early afternoon in an old-school Italian restaurant round the corner from his west London home. Cave is suited and booted as ever: not dandyism, he says, so much as “a sort of symbol of respect for the work at hand — which might be life.” He adds drily: ‘My mother used to say she insisted on always changing her underwear in case she had a car accident. I don’t want to go out wearing… lycra.”

I raise with him that idea of a persona — and wonder if it’s something that suits him or that traps him; whether it’s a version of himself or an escape from himself. “I just feel like I’m Nick Cave, and that’s the end of it,” he says. “You know, it’s not like I become something when I walk out the door. I’m just who I am.” That’s not quite, as I read it, the 2014 position.

And the frenetic, rapturously emotive performer is at least to one side of the quiet man sipping fizzy water at the table. One to one, Cave is — if not shy, exactly — painstakingly thoughtful. His conversation is quiet, hesitant, earnest and filled with qualifiers of the “kind of,” “sort of,” “does that make sense?” kind.

“I guess I was trying to say that rock stars shouldn’t get too complicated,” he says of that conversation with Winstone. “They should remain cartoon-like, easy.” But he prefaces this remark with the words: “What you have to remember is, at the time I was saying this was before… certain things happened to me.”

I think, by this understated phrase, he means the detonation of grief in his own life. In 2015 Cave and his wife, the designer Susie Bick, lost their fifteen-year-old son Arthur in an accident. Earlier this year Cave’s thirty-one-year-old son Jethro, from a previous relationship with the model Beau Lazenby, also died. Cave won’t speak publicly about Jethro’s death out of respect for Lazenby’s feelings, but the loss of Arthur was a grief that Cave worked out in public — in his two most recent Bad Seeds albums, Skeleton Tree (though most of that album was written before Arthur’s death) and Ghosteen, and in a documentary film, One More Time With Feeling.

Like it or not, Cave — who even before his loss was a novelist, screenwriter, composer and occasional actor — is complicated; and he has changed. There can be few major artists who have had such a drastic rearrangement of their relationship with their audience. When he started out as lead singer of the post-punk outfit the Birthday Party in his native Australia, the band acquired a reputation for the sheer ferocity of their live shows. They went on stage drunk and high and half the audience turned up in the hopes of having a punch-up with the singer, who often obliged them. Cave is sixty-five now, and his shows are something more like religious experiences. He talks about seeking the experience of “awe” — and describes finding it everywhere from the Halloween service at his local church to Elvis’s final concerts at Vegas.

“Things happen to everybody that eventually should, I guess, turn you into an actual person,” he says of that shift. “When I was young I was just a kind of unformed human being, with the emotional range of, you know, a ten-year-old. Now I have the emotional range of maybe a thirteen-year-old.” He says, at another point: “As you get older, you start to look at [your work] in terms of — what benefit is it to the world rather than just yourself? That self-absorption you have as a young person, where you’re just sucking up the world and everything in it, and you’re becoming full of art… this thing disappears. And that becomes less important. You need to be able to turn that around and turn your attention back on to the world, with all your talents in tow.”

His relationship with his audience was one of the things that helped to bring him through the grief. He started a blog called the Red Hand Files in which he replies with great openness and honesty to questions from fans. His decision to grieve in public: was that one that was forced on him by his visibility, or was it a conscious choice?

“It’s hard to remember what happened,” he says, “but the little momentary sparks of light that happened in a very dark time were coming from my fans. Or not even my fans: just people writing to me, saying: ‘Look, we know what you’re going through.’ I got just endless mail. It wasn’t just letters of condolence, but letters saying: this happened to me, I lost my child, or I lost this person. That had a profound effect on me ultimately. I just found that incredibly helpful. On some level, it was good for me that I did it publicly. Because I got so much back from other people.”

“One thing that’s happened,” he adds, “which is kind of lovely but also problematic, is that people feel more inclined to tell me their problems. I’m at a party and six people will tell me about how they just lost their mothers. People are very open about things with me, and I’m open within the Red Hand Files and in interviews — but as a human being I’m actually not. I’m quite reserved. But now I’m like a walking agony aunt or something.”

His songwriting has changed, too. For much of his career Cave wrote story-songs full of pantomime menace, black humor and the trappings of nineteenth-century gothic Americana: blood, roses, hellfire preachers, femmes fatales and dusty-booted cowboys. It’s an odd idiom for an Australian former choirboy — Cave grew up in the backwater town of Warracknabeal — to have made his own. “I wasn’t particularly interested in my own culture in Australia,” he says, “which was quite normal for Australians at that time because, on some level, we didn’t have our own culture. We grew up on American TV, listening to American music. When I first went to America, someone American asked me: ‘Why do you always make American music?’ I was taken aback because it never occurred to me that was the case.

“At the same time, I also listened to a lot of country and western as a young person. Even when we were listening to punk rock, we were listening to country; Tammy Wynette and all this other stuff. Then I discovered blues music. And that changed things considerably. And along with that came Southern Gothic writing. All of this built up a kind of artistic language I used.”

He used to write songs and present them to his band. Those last two Bad Seeds albums are spare, ambient, haunted, and frequently improvisational — “Essentially, they come out of me and Warren [Ellis] sitting around in a room together: he sits there playing his keyboard and I sing on top of it and play the piano. Most of it’s unlistenable, but occasionally really beautiful things happen.”

The magic, as Cave sees it, happens bet-ween words and music: “I’m basically a songwriter. The reason I say that is because there’s a whole load of stuff that I write that I know doesn’t stand up on the page, and doesn’t need to stand up on the page. It sounds great when you’re singing it, but you don’t want to have to read it. Some of my very favorite songs, and the songs that mean a lot to people and have an enormous emotional tug, are poetically the most underwhelming. This song, ‘I Need You,’ is just improvised completely. Most of it doesn’t really make sense. And I just didn’t fix it up, because it’s a one-take thing, it just has this pull. And it’s something to do with song and words together, which as a piece of writing on its own doesn’t even bear consideration.

“Yet it is really one of the most loved songs for both myself and my audience. For me, these are songs: they’re sort of buoyed along by the music and the way that something is sung. In that respect I don’t really consider myself a poet. I see myself as a songwriter. And I don’t see that, by the way, as a lesser form, or a kind of poor man’s poetry.”

I know through a mutual friend that we share an enthusiasm for the American poet John Berryman, whose Dream Songs Cave confirms were “a big influence — that sort of fractured narrative” on his songwriting work. I wonder what he makes of Berryman’s dictum that “the artist is extremely lucky who is presented with the worst possible ordeal which will not actually kill him. At that point, he’s in business.”

“I don’t see the loss of my son as a theme,” he says. “I see it as a condition of being. That’s what loss ultimately is for us all: it’s a thing that we become — an amalgam of our losses. It’s not like: great, I have my theme to write about. I don’t feel that in any way at all. I just feel the temperature of my writing changed completely after Arthur died. It became concerned with different things. But I do agree with [Berryman] in the sense that you can… you can be obliterated, and be forced to put yourself back together again, and you can put yourself back together again in a way that allows you a kind of freedom to express yourself in other ways.”

Cave is so unusual, as rock stars go. Religion goes through his work, and as substance rather than set-dressing. Indeed, he has said that during the depths of his heroin addiction thirty years ago, he would go to church in the morning before he visited his dealer, as if the two activities balanced each other out. But Cave isn’t buying my theory that addiction and religious faith are different versions of the same psychological impulse.

“I never saw it like that,” he says, “but as a heroin addict, there was something about the habit and the ritual that was religious, in the sense that it was sort of structural to your life; it held everything together. It fed into having a structured life. Heroin in particular — I don’t know about alcohol, because alcohol is essentially chaotic: you don’t know what’s going to happen next. Heroin, you do know what’s going to happen next, provided you don’t die. You just take it and it’s pretty harmless.”

He swiftly corrects himself, presumably knowing how that might look quoted out of context — “I don’t mean the drug is harmless” — and then tails off. Certainly, his view is that with heroin at least most of the harm comes from its illegality. But he got clean through Narcotics Anonymous and he speaks with fervent approval of the fellowship. It’s just one example he offers of what he calls the “utility” of belief.

Cave had a conventionally churchgoing upbringing in a not particularly religious household, but says: “It’s clear to me now that I’ve always had a religious temperament. I’ve been interested from as far back as I can remember. But I’ve always also felt like I could never quite find my way to believe in it wholesale. So it’s always been a struggle. But the more I go on, the less of a struggle it is. I think that to believe is essentially good for you. I’ve certainly found it in that way, even though we may be believing in something that doesn’t exist.” Echoing Dennis Potter’s line that religion “isn’t the bandage, it’s the wound,” he says: “I’ve just come to understand that the struggle itself, for me at least, is the religious experience.”

In Faith, Hope and Carnage, he exiles himself even further from the mainstream of the rock-star tribe by describing himself as a conservative. He clarifies, when I look like I’m about to blame him for Liz Truss, that he’s not a paid-up member of the political party, but says: “In regards to economics I guess I’m on the left but culturally I would say I’m a conservative. I have a deep love for a lot of art that feels, at this point, in a precarious situation. I just think that the art that we have is the very best we can do most of the time. To be casual about it — about whether it should exist or not, or what art should exist or not — is something we do at our peril.”

Accordingly, he’s a critic of cancel culture. “Over issues on free speech, I would say I’m conservative… It’s a difficult thing to talk about because I’m not kind of this ‘anti-woke guy’ or anything like that. But I feel on some levels politically homeless, in the respect that I just don’t buy a lot of what’s going on in the left.

“‘Anti-woke’ is an industry too. You see these various places that are both stoking the culture wars and complaining about them at the same time. It’s a business to keep the culture wars alive on both sides. I’m a little cautious about being caught up in the middle of it.”

He says he doesn’t feel, as some do, the pressure to censor himself. Would he think twice about writing his version of the traditional folk song “Stagger Lee” — a raucous comic ballad involving sexual violence – for instance? “I’ve played ‘Stagger Lee’ maybe 2,000 times, and I’ve never seen anyone look at me with anything other than pure delight on their faces when we play that song.”

Cave’s change of direction is one that, he admits, has left some of his traditional audience behind. “There are a lot of people who just wish it was like the old days,” he says. “But there’s a lot of people who just wish their lives were like the old days in general. They see change as a personal slight. Our audience has almost completely changed live. There’s all these young people who don’t care about the history of the band, don’t care about those old songs in the same way, they don’t require that we play them. They just love the new stuff.

“Just the looks on their faces are something else. They’re confused by what’s going on on stage. The big frontman type of thing is maybe a thing of the past: that direct approach we have — the touching, leaning in… I just don’t think they’ve really experienced something like that before. They’re crying and they’re laughing and they’re scared and they’re bewildered. It’s quite something.”

Bob Dylan was in the UK shortly before we spoke. When I ask Cave whether he understands what it is that makes Dylan, at eighty-one and presumably in no need of the money, continue playing hundreds of nights a year, he doesn’t hesitate. “Yeah,” he smiles. “Yeah. I do understand that impulse.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.