If you’re one of the many people worried that US foreign policy is in the hands of a visibly declining eighty-one year-old president, Alexander Ward’s account of the Biden administration’s first two years in office may — or may not — make you feel better, for he leaves readers with little doubt as to who is actually the executive branch’s most influential decision-maker: forty-seven year-old national security advisor Jake Sullivan.

Ward might deny any such authorial intent, but time and again he shows his hand, as when he invokes “Sullivan’s first two years at the helm alongside Biden.” Secretary of state Antony Blinken is of course close on Sullivan’s heels, but Ward’s thoroughly reported book, along with Chris Whipple’s similar tome from early 2023, The Fight of His Life, both remind anyone tempted to forget that the calamitous August 2021 US withdrawal from Afghanistan remains the defining event of Joe Biden’s first term in the White House.

Biden’s insistence on withdrawing all US forces and supporting contractors from Afghanistan took place over the objections of all the relevant uniformed military commanders. Ward reports that Biden had made up his mind on that course of action back in 2009, following a trip there early in his eight-year tenure as Barack Obama’s vice president. Ward adds that both Sullivan and Blinken “were disillusioned” that Obama failed to follow through on his own desire to abandon Afghanistan, and two months after assuming the presidency in January 2021 Biden publicly proclaimed that “we will leave” and promised that “we’re going to do it in a safe and orderly way.” He reiterated that commitment in mid-April, insisting that “we will not conduct a hasty rush to the exit. We’ll do it responsibly, deliberately and safely.” As Ward reminds readers, “the last thing anyone wanted was a rushed American exit that echoed the scenes of Saigon in Vietnam thirty years earlier” when a lone CIA officer hustled people into a helicopter hovering over the roof of the US embassy.

Throughout spring 2021, uniformed American commanders “advocated for an indefinite military presence” of at least 2,500 troops, with Joint Chiefs of Staff chairman Mark A. Milley presciently warning Biden that “withdrawing American forces would make it easy for the Taliban to retake the country” and that if that indeed did come to pass, Afghan “women’s rights ‘will go back to the Stone Age.’”

Milley was far from the only well-informed observer who envisioned what could happen. In May former US ambassador Ronald Neumann warned publicly of the danger of a rapid Taliban advance once US forces retreated: “If multiple cities fall the game may be over, and a rapid unraveling of the Afghan army and the Kabul leadership becomes a possibility.” Perhaps even more essential to the Afghan forces than US troops were the US contractors who maintained Afghan equipment, especially its air force, but Biden’s withdrawal order covered them as well. Once US soldiers began pulling back to Kabul from important bases, so did the contractors. Former CIA analyst Bruce Riedel noted that “the contractors would’ve stayed if they hadn’t been told they had to leave” and emphasized to Whipple how “in that sense, we self-destructed our ally.”

By August, the rout was underway, with the husk of American troops and a handful of remaining diplomats all huddled at Kabul’s large international airport. Ward writes that for Biden, “the withdrawal from Afghanistan … was threatening to be the noose around his presidency,” and as hurriedly organized evacuation flights departed from the increasingly beleaguered airfield, it became obvious to the entire world “how unprepared the United States was for the advance of the Taliban and the extraction of vulnerable Afghan allies.” Then, as a modest number of US troops struggled to maintain control of the surging crowds hoping to make it into the airport and onto a departing plane, a suicide bomber struck just outside the gates, killing not only scores of desperate Afghans but thirteen US service members.

That news left Biden profoundly shaken: “The worst that can happen has happened.” Whipple observes that Biden “appeared dazed, almost shellshocked,” adding that “both the decision to withdraw and its flawed execution belonged to him.” Ward similarly concludes that the debatable merits of that decision “would pale in comparison to the scenes of large-scale human suffering in Kabul.” That Biden “had ended the war wouldn’t be his legacy. How he ended the war would.”

On August 29, the coffins containing the remains of those thirteen US heroes arrived at Dover Air Force Base, where both their survivors and the president somberly greeted them. Three of the families were infuriated at Biden, with one relative yelling, “You can’t fuck up as bad as he did and say you’re sorry. This didn’t need to happen.” Another screamed within Biden’s earshot, “I hope you burn in hell.” Former defense secretary and CIA director Leon Panetta, a Democrat, admitted to Whipple that “I refuse to believe that we couldn’t have done this in a better way” and Whipple’s own conclusion is almost undebatable: “The Afghanistan withdrawal was a whole-of-government failure; everyone got nearly everything wrong.”

But within Biden’s White House, literally no one was willing to acknowledge as much. “There was never any serious reckoning inside the administration,” Ward reports, and “no one offered to resign in large part because the president didn’t believe anyone had made a mistake,” including himself. “They all knew their reputations would take a huge hit,” Ward adds, and for Sullivan it was “the greatest failure of his professional career,” but their utter inability to muster up even a shred of self-criticism reached its unbelievable apogee a few months later when Sullivan publicly declared that “I believe, fundamentally, that the United States is in a better strategic position than the day we took office” eleven months earlier.

Such self-regard was all but delusional, yet Biden’s inner circle knew, as Ward notes, that “the press… would eventually move on” from the awful tragedy of Kabul, which of course proved true: coming up on three years later, US press coverage of Afghanistan and the millions of Afghans who had hoped to live far better lives free of a misogynistic religious cult is virtually nonexistent.

Biden had entered office thinking that “competing with China would be the defining challenge” of his presidency, and Sullivan envisioned creating a “foreign policy for the middle class” that “prioritized the domestic elements of foreign policy.” That was admittedly an electoral political strategy, not a vision of how best to steer world affairs, and by late 2021 growing evidence of Russian military plans to invade Ukraine threatened a second crisis that would divert US attention from China.

Back in 2014, when Vladimir Putin’s nationalist dictatorship seized Crimea and eastern portions of the Donbas from Ukraine, “the Obama administration did little in response,” Ward reminds readers. Vice President Biden had sought more, and during his eight vice-presidential years he made six visits to the fledgling democracy. In December 2021 Sullivan publicly warned that “things we did not do in 2014 we are prepared to do now.” As 2022 dawned, Ward notes that it was clear that “the Obama-era modus operandi of risk aversion was gone.”

Ward opines that the new Ukraine crisis “was the Obama cohort’s chance at redemption,” yet as Whipple earlier reported, Biden himself “was preoccupied with the possibility that Putin might use a nuclear weapon.” Ward fully concurs, quoting Biden as saying, “We don’t want World War Three.” His administration believed that “war with Russia had to be avoided at all costs,” yet why surrendering Ukraine — and potentially other nations, such as highly vulnerable Moldova — to Putin’s rampant, Nazi-like aggression would be preferable to a nuclear faceoff appears never to have been debated.

Purposeful leaking of detailed US intelligence exposed Russia’s invasion plans, but come early morning on February 24, Russian forces nonetheless streamed into Ukraine from multiple directions, highlighting the United States’s “inability to stop a war” that everyone other than the unduly hopeful Ukrainian leadership had clearly seen coming.

Ward asserts, somewhat puzzlingly, that the Biden administration wishfully believed that no matter how military events played out, “the US-led resistance and world order wins. Democracy wins. Russia and Putin’s brand of authoritarianism, if not Putin himself, loses.” If taken at face value, that attitude evinced no more concern for millions of brave Ukrainians than had the Biden mindset six months earlier for legions of desperate Afghans. Though Ukrainian courage and skill halted and defeated the Russian advance on Kyiv, within weeks it was clear that the Russo-Ukrainian war would endure for many months and most likely years.

Ward reports that in late March 2022, General Milley advised Biden, “‘You have to answer the question of why this war should matter to the American people and what the war is about.’ ‘OK, what is it about?’ Biden asked.” Ward gives no indication whether that reply was the response of a Socratic questioner or an earnest dunderhead. Preserving world order, Milley answered. “That’s good,” a Biden aide responded. “I’ll put that in there.”

Some months later, Biden would make the decision to visit Kyiv in person, an unprecedented appearance by a sitting US president in an active war zone, and US funds and material would go a very long way towards sustaining Ukraine’s defensive military successes throughout 2022 and 2023.

But as the duration and sufficiency of US military support for Ukraine came into question during the early weeks of 2024, the issue of whether Biden could successfully compromise with congressional Republicans to keep that necessary support flowing became existentially acute. Ward accurately poses the fundamental question that remains: “Ukraine would determine the president’s legacy. Would he be remembered for the disastrous withdrawal from Kabul,” or instead for successfully preserving the sovereignty of a vibrant European democracy from Hitlerian aggression?

Like almost all contemporaneously reported books of its genre, The Internationalists inescapably suffers from how much of its narrative depends on background sourcing, where Ward is unable to attribute quotations by name, but only to a “senior administration official” or someone “familiar with” Jake Sullivan’s thinking. Whipple, in The Fight of His Life, had somewhat greater success in getting Biden officials to speak on the record, but influential yet highly press-averse figures such as defense secretary Lloyd Austin are always eclipsed in such instant histories.

A decade ago, former US defense secretary Robert M. Gates famously wrote of Biden, “I think he has been wrong on nearly every major foreign policy and national security issue over the past four decades.” Biden’s abandonment of Afghanistan reinforced that historical verdict; only Ukraine’s future will decide whether that judgment is yet further buttressed or decisively contradicted.

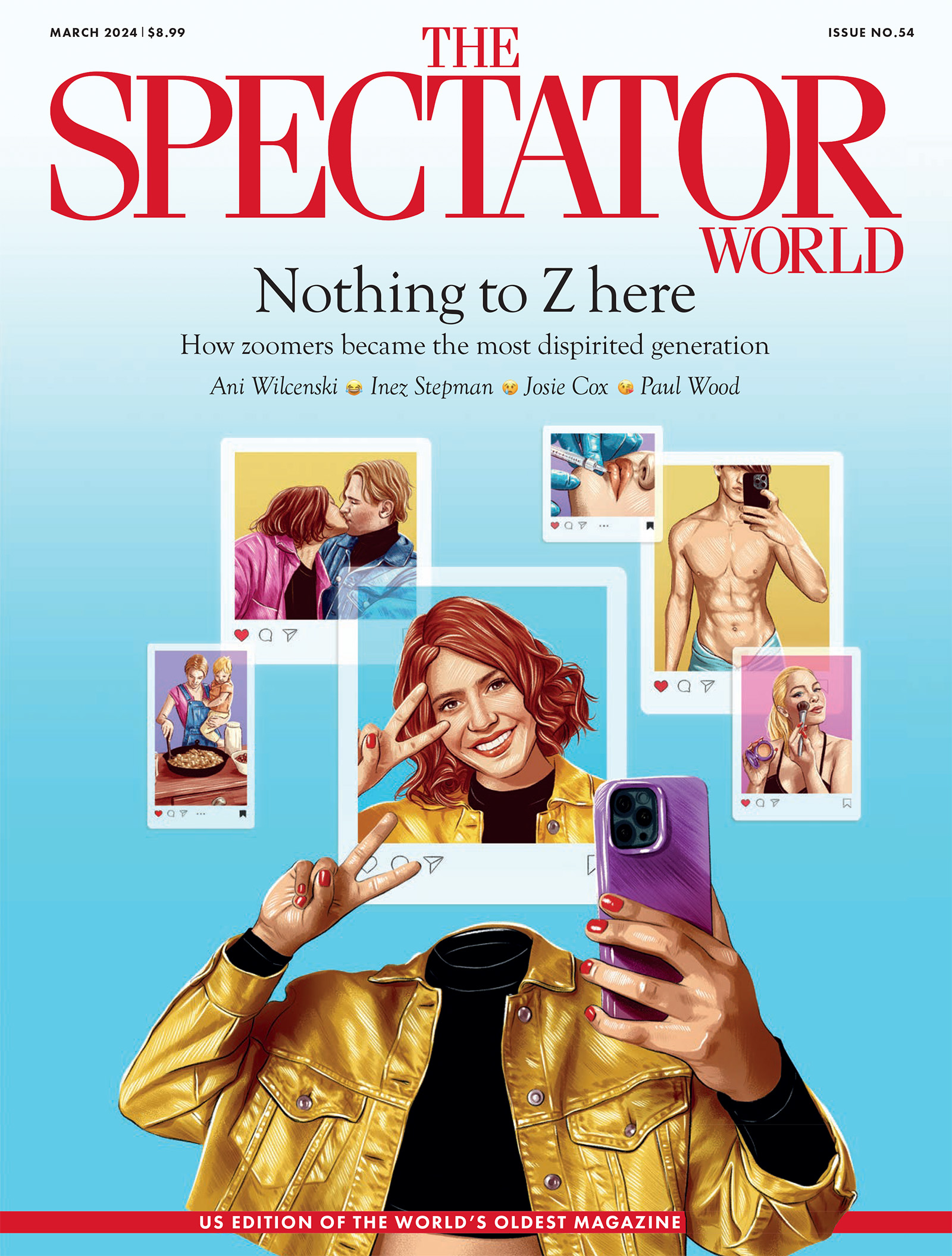

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2024 World edition.