There is a girl on TikTok, a bleached-blonde New York transplant who just passed a million followers, whose videos I cannot stop watching. The secret to her rise was “Get Ready with Me” storytimes in which she sat in front of the camera applying mascara and retelling — in painstaking detail — her lurid misadventures. Some highlights: throwing up on a guy’s bed after a wine-fueled hook-up and then realizing he had a girlfriend of two years, battling Montezuma’s revenge at a restaurant in Cabo, getting a UTI so bad she thought it was a kidney infection, inadvertently shipping a ton of “hot girl summer whore clothes” to a guy whose white sheets she bled all over after acquiring a polyp.

I would rather chop my own feet off with a butterknife than publicly claim one of the stories mentioned here. But I’m the one juicing her view numbers as I gawk in horror from the couch while she’s laughing all the way to the bank with a check from a leggings company. If anything, her instincts are right — these days, you can be rewarded handsomely for oversharing online, granting people access to your insecurities and anxieties and quirks in exchange for a six-figure income hawking natural deodorant on Instagram. There are a zillion reasons why this trend is depressing and concerning and will exacerbate the continued flattening of American life into an aesthetically uninteresting corporate-backed monolith, but for now let’s focus on one: the tragic cultural death of mystery.

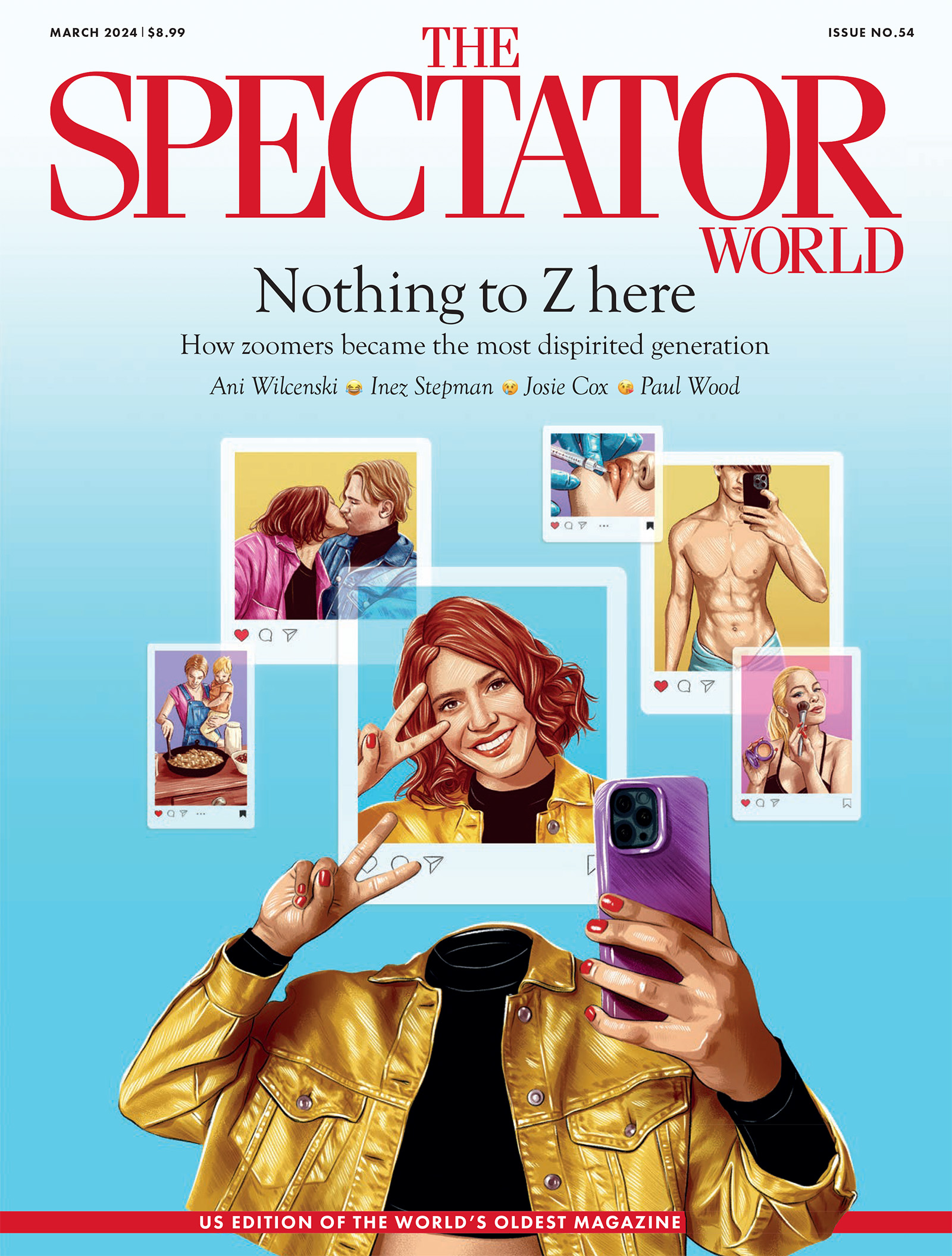

My age group, Generation Z, is the least mysterious generation on record, and it’s not just the influencers — we all curate our Hinge profiles, we telegraph our politics and playlists on social media, we “normalize talking about” everything from our stomach issues to the inner workings of our sex lives, and we invoke our “lived experience” to establish our authority everywhere from the classroom to the workplace. And we are also having the least sex of any generation in recent memory. Commentators have a lot of theories why — increased time spent online, a pandemic-driven “failure to launch,” the generous assessment that we just have a more enlightened idea of consent. But I’d argue that the answer is overarching, which is that our cultural relationship to mystery is broken — and we’re sexless and suffering because of it.

Last year, I read an excellent essay in Tablet tearing into the sex positivity movement, which the author Ginevra Davis criticized as a fundamentally unsexy “long march towards demystification.” What’s so horrible about demystification, a critic might ask. Isn’t it good to dispel some of the taboos surrounding sex? Haven’t women been going around having bad sex with no idea how to speak up for themselves for way too long?

Sure, but there’s a difference between creating a societal environment in which everyone feels safe and empowered and creating a societal environment in which people are building business empires through gratuitously salacious sex podcasts or (this happened in one of my writing classes at Columbia) writing ten-page personal essays about hooking up with a Grindr match in a bathroom at JFK Terminal 5. The problem with all this normalizing and demystifying is that too much information runs counter to the very nature of desire. It’s a lot less interesting to learn about someone from something they blurt out in group conversation or telegraph on the internet than it is to discover it with them, slowly, on your own.

You can take this from Esther Perel, the psychotherapist whose cross-cultural work on intimacy has made her a global authority on relationships and sexuality. In Mating in Captivity, her bestselling book on the paradoxes within the erotic, she writes about the danger of pseudo-transparency, when couples approximate “intimacy” by learning every minute fact about their partner’s lives. As she explains:

When the impulse to share becomes obligatory… it is the kiss of death for sex. Deprived of enigma, intimacy becomes cruel when it excludes any possibility of discovery. Where there is nothing left to hide, there is nothing left to seek.

Perel also underscores the necessity of maintaining a “secret garden” — a private “physical, emotional and intellectual” space belonging only to you, which will paradoxically strengthen someone’s draw toward you as you nurture it on your own. “Not everything needs to be revealed,” she writes.

Not everything needs to be revealed. So many of Gen Z’s dilemmas boil down to this problem. We’re meeting people with the assistance of the internet, where there is far too much information already and a subsequent lack of mystery. The problem is everywhere, from curating detailed online dating profiles in hopes of finding a lover to the much-repeated male complaint that they’re turned off otherwise interesting girls by their overzealous internet presences.

My favorite example of the lack-of-mystery phenomenon manifests in one of the biggest online dating complaints from women: finding an apparently eligible man and then realizing he follows way too many girls on Instagram. It’s one of those hyper-online issues that feels like a meme (“Imagine explaining this to a Founding Father”), but women bemoan it constantly because it happens constantly — you meet or match, you conduct the customary stalk of his social media, you see a column of thirty bikini-clad women, you get a gross feeling in your stomach, and suddenly the initial excitement is gone. Every minute, somewhere in the world, a girl is getting mad at her boyfriend for liking thirst traps on Instagram. Perhaps a girl in a “talking stage” is checking her suitor’s following list (which she likely has memorized) to see if he’s added any new girls so she can stalk them and see if they might be in contact. I have lived through this psychological torment — last year I was seeing a man whose female follows were burned into my brain, to the point where I saw one of them drinking an Aperol spritz at a bar, realized she was skinnier than me, and nearly cried in the bathroom.

Of course, everyone knows by now that social media is not objective reality, so why are these stupid little things such an issue? Because we’ve come to regard people’s internet presences as an extension of themselves, and we use them to gain a window into their “secret gardens” in the absence of opportunities for genuine connection. When we see a man’s “following” column jam-packed with women, we infer that he’s either playing the field or he’s weirdly thirsty. If the girls look just like us, we feel way less special, and his interest feels less meaningful. If we can find a digital record of his previous involvements, we can start probing into his past, giving us less to learn from him directly. Sometimes we’re woefully wrong — my run-in with the Aperol spritz girl culminated in my confronting the man in question, who was wildly creeped out and informed me that he’d never even met her — but the real problem is not who is on the right side of Instagram history. The problem is that we have access to all this information, useful or otherwise, that we really should not have, and it’s messing with our minds.

Perhaps a lack of mystique can sometimes save us from getting involved with a digital stranger who turns out to be a creep, but it can introduce unneeded doubt or misgivings about a person who could turn out to be genuinely off-the-internet cool, dooming a relationship before it has a chance to begin. This broken relationship to mystery is a paradox, with both sides undersexed. The overabundance of information can scare us away from people, but it can also create a dangerously intoxicating digital allure. After all, desire is energized by distance and elusiveness — and there’s no better way to unite those powerful forces than lusting after hot people online.

Much has been made about the psychological effects of Gen Z’s internet-dwelling — the Pornhub obsession, the endless swiping with no desire to meet in person, the thirsting over airbrushed Insta baddies you’ll never know in real life, but you feel like you do because you saw them make their favorite smoothie on their story this morning. And all this, too, comes back to mystery — we’re programmed to gravitate toward it, and in a culture where people’s inner worlds are as accessible as they’ve ever been, the pull of an elusive digital stranger is doubly intoxicating. The oversharing that might be off-putting from someone you actually meet feels entirely different from what happens with someone you’ll never have to get to know. Now, the novel they’re reading or the pasta they’re cooking becomes an endearing personal detail — never mind, of course, that this girl most definitely doesn’t spend all her time going to art exhibits and reading Capote on windowsills, as nice as that looks on an Instagram post, and as lovely as it is to fantasize about such a person from afar. It’s certainly a lot lovelier and easier than contending with all the complexities and sharp edges of real life.

Take all of this — our natural predisposition toward the unknown, our countless opportunities to fantasize about unknown quantities online, the ability of internet fantasizing to subsequently warp our perception of reality — and it’s no wonder Gen Z isn’t getting laid. Why go through the trouble to meet a real-world person, when the digital world has never been more appealing, and the lived world has never been less sexy?

How do you restore sexual mystique to the most undersexed age group in hundreds of years? The answer here, too, lies in fixing our broken relationship to mystery. Stop swiping mindlessly on beautiful, removed strangers you have no desire to meet. Spend less time fantasizing about Instagram models whose inner lives you’ll never know. Share less personal information with people who don’t actually care.

That time would be better spent committing yourself to the process of mutual discovery and learning to appreciate the surprises and upended expectations that come when you do — many times you’ll find them more interesting than the visions you had in your head. It would also be well spent nurturing your “secret garden” by doing something that you don’t share with the world, as funny or internet-lucrative or alluring-to-potential-lovers as it might be.

As Esther Perel observes,

Desire needs mystery. Love likes to shrink the distance that exists between me and you, while desire is energized by it. If intimacy grows through repetition and familiarity, eroticism is numbed by repetition. It thrives on the mysterious, the novel, and the unexpected…An expression of longing, desire requires ongoing elusiveness. It is less concerned with where it has already been than passionate about where it can still go.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2024 World edition.