After three days of voting, the polls close today in Egypt’s presidential elections. The result is expected on December 18, but voters already know there can be only one winner: President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, who has been in power for nearly a decade. The other candidates for the presidency (those permitted to stand against him) aren’t really running to win but are simply there to make up the numbers and help create the impression that voters are being offered a choice. This sham of an electoral process reveals much about Sisi’s iron grip on the country and its main organs of state, including the much-feared security services.

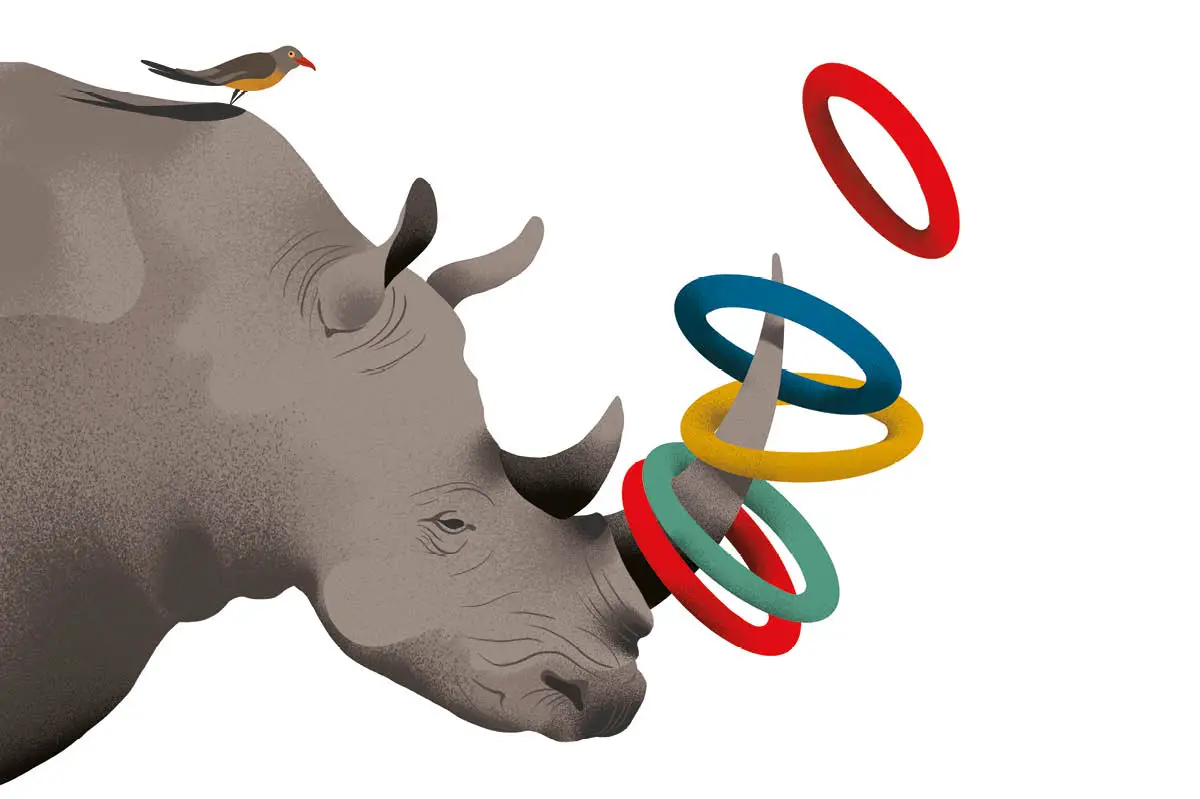

After seizing power in a military coup in 2013, Sisi won two presidential elections in 2014 and 2018, both with 97 percent of the vote. These astonishing numbers are hardly surprising given what happens at election time in Egypt. In the 2018 election, the only other candidate standing — Moussa Mostafa Moussa — openly supported Sisi’s rule. It was a non-contest labeled as “farcical” by critics. The 2018 shambles prompted a change of approach for this time round, with the authorities determined to have a multi-candidate process to give the impression of a real electoral contest. But this has fooled no one — it is all for show.

The widespread voter apathy stings Sisi because it undermines what little claim he can make to democratic legitimacy

The main potential opposition candidate, Ahmed el-Tantawy, a former Member of Parliament, was forced out of the race early. He claimed security forces had arrested dozens of his supporters and blocked him from holding campaign events. The authorities dismissed all his accusations as baseless. He is now facing trial for allegedly circulating election-related papers without permission. The three remaining candidates in the election have a low public profile with little in the way of significant support expected for any of them. This is what passes for a fair and free election in Egypt.

The only real question is how many voters will bother turning up at the polls, given that the outcome appears predetermined. Voting had to be extended in 2014 for an extra day to help boost the numbers. Four years later, in 2018, the turnout was a lowly 40 percent. There have been reports in the past of bribes, involving money or food, to help encourage voters into the polling booths. This widespread apathy amongst voters stings Sisi because it undermines what little claim he can make to democratic legitimacy.

Sisi can conspire to win as many elections as he likes but this will do nothing to hide the dire state of Egypt after his decade in power. Official figures show that nearly a third of the country’s 109 million population lives below the poverty line. Its currency has lost more than half its value over the last year or so. A further devaluation is widely expected after the election. Inflation is running at just under 35 percent, with food inflation even higher. Egypt stumbles from one IMF bailout to the next.

Even so, there appears to be no lack of money when it comes to funding the growing number of political vanity projects dear to Sisi’s heart. These include a $8 billion expansion of the Suez Canal, and the building of a new administrative capital on the outskirts of Cairo which is expected to cost $43 billion. Anyone who dares to question the decisions or actions of those in power is crushed without mercy. Sisi’s political foes languish in Egypt’s notoriously brutal prison system. Human rights groups have accused the security forces of carrying out arbitrary detentions and torture with impunity. The regime continues to maintain that there are no political prisoners in Egypt.

All in all, it is a grim state of affairs. Long gone is the heady idealism of the 2011 “Arab Spring” uprising, when Egypt’s long-suffering people demanded democracy and an open society with greater freedoms and rights. They have ended up with Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, who shows no sign of departing the scene any time soon.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.