Two thousand among the great and the good from around the world will soon receive a letter from King Charles III and Queen Camilla. The invitation to the coronation on May 6, which was unveiled Wednesday, is not what people might have expected. Elizabeth II’s coronation invitation was formal, and, even by the standards of 1953, old-fashioned: it looked like the sort of thing that Victoria would have issued for her eventful, near-disastrous ceremony over a century before. The implication was clear, namely that her reign would be a formal, decorous one, firmly in keeping with the high ideals of her predecessors, and it proved an apt portent for her highly successful time upon the throne.

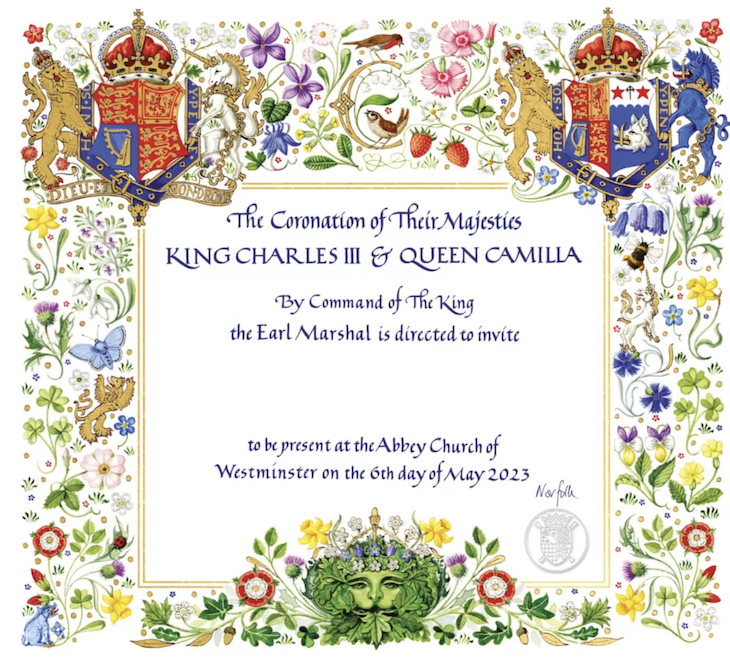

Yet if she saw what her son had come up with, she might have gasped with surprise, and then smiled in wry recognition. The invitation — designed by the heraldic artist Andrew Jamieson — is a riot of color and celebration. Among the many items depicted is everything from the four national flowers of the United Kingdom — the rose, shamrock, thistle and daffodil — to the coats of arms of both King Charles and Queen Camilla. The invitation pointedly invites the guests to the coronation of “their Majesties”; it is clear that this will be a dual monarchy, rather than the constitutionally unequal relationship between Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip, something that rankled throughout their marriage.

The design pays explicit homage to Charles’s own invitation to his mother’s coronation, sent when he was four: rather less formal than the official version, it was similarly colorful and depicted soldiers, trumpeters and a lion and a unicorn amid verdant foliage. Although Jamieson claims not to have seen the prince’s invitation, the design is well-known — reproductions are readily available from the Royal Collection — and it’s inevitable that Charles meant to summon up memories of his own joyful experiences seventy years ago.

The Duke has still made no public comment on whether or not he will be attending the coronation

And there is something more pagan and less predictable lurking, too. At the bottom of Jamieson’s artwork is the prominent symbol of a green man, a representation of rebirth and of spring emerging out of winter and darkness. Although the artist has called its inclusion “just a fancy,” such a symbolic representation of what is clearly intended to be a new reign, for a new kingdom, is hardly present by accident. King Charles has been preparing for his stint as monarch for decades, and ever since his bold, daring King’s Speech last Christmas, we have been briefed that he will be a different kind of ruler — someone attuned both to the demands of the modern world and also deeply in touch with an almost mystical sense of what his country is. (It would be no surprise to discover that the king had seen Jez Butterworth’s play Jerusalem, itself imbued with a mythic love of Britain and its history and lore.)

Amid all this excitement and optimism, there is an inevitable difficulty — and it comes in the form of Prince Harry. The Duke has still made no public comment on whether or not he will be attending the coronation, and, with the event a matter of a few weeks away, it seems inevitable that he will have made up his mind one way or the other by now.

For all of Harry’s much-vaunted love of “transparency,” his refusal to announce whether or not he will be present for his father’s coronation — and, indeed, whether he has received one of the carefully designed invitations — suggests that his gamesplaying has not come to an end yet. The invitation may suggest that the ceremony should usher in a new era in royal life, but until this particular difficulty is resolved, it is inevitable that the resentments and score-settling of the past will continue to dominate all.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.